Image and subsequent information from "Harald Damsleth."

Click to enlarge.

On the snowy companion cover of the magazine that brings him his picture of the girl, the soldier reads his letter. Behind him is a shattered tree; in front of him, at the ready, is his rifle, a Karabiner 98. His eyes are hidden by his helmet, but on his mouth is a half-smile. His uniform is white camouflage, but his hands are swaddled in black. It is (and the angles of helmet and letter direct our eyes to it) the black of a pair of mittens, knitted in a traditional Norwegian snowflake pattern. Like the girl's world, the soldier's world is unmoving. There is no retreat on this front; only, in the long shadows of a northern winter, white letter and black mitten and the stationary idea of home.

The soldier would have been a member of Hitler's SS Wiking Division, a body of Norwegian fascist volunteers that spent most of World War II on the Russian front. The magazine which helped him see himself and his girl this way, static obverse and reverse, was published for him by the Nasjonal Samling ("National Gathering"), Vidkun Quisling's Norwegian Nazi party. Its full title was Austrvegr: manedsblad for frontkjempere og germansk landtjeneste -- that is, "Austrvegr: A Monthly for Front-Line Fighters and Germanic [not 'German'] Servicemen." However, that word in the main title, Austrvegr, in its runic font on the background of a highway sign, isn't Norwegian but Old Norse. The ancient term literally translates to "Eastward Road," but in the sagas it refers to the east generally and, often, to Russia specifically (Jakobsson).

Like the philological and racial term germansk in the magazine's subtitle, the magazine's antique name is probably symptomatic. I'd guess that it could be placed in a continuum with the Malatesta cantos of Ezra Pound, the vast collection of Americana at the Henry Ford Museum, T. S. Eliot's fugitive Criterion essays in mystical praise of folk dancing, and the archetypal psychology of Jung. All such accumulations of feeling can be considered expressions of twentieth-century conservatism's yearning for the mythic and the authentic -- and a soldier taking part in a long retreat across a white hell certainly would have a mind full of yearning. It seems to have been the mission of Austrvegr to translate that yearning into determination and confidence. For that morale-building purpose, the magazine's title spoke the language of Norway's Viking myth, and its covers illustrated that language in broad strokes containing and controlling washes of unambiguous primary color.

The cover's illustrator, Harald Damsleth (1906-1971), was helped to paint those broad strokes by an aesthetic which shaped itself around his politics. With a German mother, a German wife, and an education from a German school of commercial art, Damsleth had joined the Nasjonal Samling as early as 1933, and after the German conquest of Norway in 1940 he became one of the Quisling regime's most prolific propagandists. Many of his former colleagues in Oslo's advertising and publishing worlds ceased to deal with him, but in his wartime designs, from posters to postage stamps, he reached back for strength to an ancient source in the Nasjonal Samling's pagan sun-circle emblem.

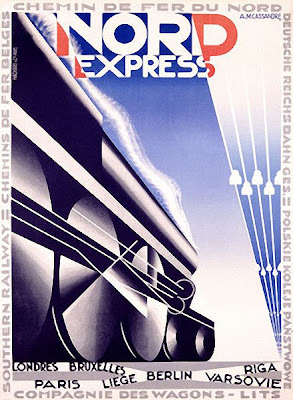

And here's something that looks like a difference but isn't: before 1940, Damsleth was an internationalist. In his prewar work, he was a magpie of Art Deco: a collector of angles and fonts and motifs whose composite designs almost amounted to plagiarism from such primary creators as A. M. Cassandre.

By Damsleth

By Cassandre. Click to enlarge.

Such unoriginality can be historically educational. The derivative, secondary forms that make up Damsleth's Art Deco seem to mean that by the time modernism reached Norway in the 1930s, it had become canonical. Because it could now be imitated in recognizable form, because it could now be understood by allusion, it could be thought of as a tradition, no more startling than the six-pointed snowflake star on the Nazi soldier's mitten. By the time they reached Damsleth's studio, the streamlines on Upton Sinclair's racing car were no longer functional but superficial. The demand they made on Norway's way of seeing was no longer an engineer's daring imperative but the merely temperamental mood swing of a fashion trend. When the time came for Norwegian style to change again, streamlining receded without a fuss before the newer trend of the folksy and the mythic.

And of course there's nothing specifically Norwegian or Nordic or Nazi about the theme of Damsleth's cover for Austrvegr. Far from home and in danger, anyone will fantasize about the place where he longs to return, and he will wish the place to be a wise, sheltering mother to his moods, outwardly impassive but secretly knitting fuzzy mittens just for him. In the United States, for instance, one of the most popular movies produced during World War II, Since You Went Away, depicts home as an impeccably hierarchical place, with Claudette Colbert and Monty Woolley dispensing their words of wisdom not in American demotic but in the Received Standard English of the Mother Country. Another blockbuster, The Best Years of Our Lives, introduces us at the start to three returning veterans, reveals them to have been respectively a member of the prewar upper class, a member of the prewar middle class, and a member of the prewar lower class, and then observes as the American class system reestablishes itself over their lives.

And, of course, The Best Years of Our Lives ends, as its art requires it to, with a wedding and a promise of more weddings to come. As Albert Cook says in The Dark Voyage and the Golden Mean, comedy is conservative. It starts with a stable social structure, upsets it by changing it (in comedy, different means bad), and then reestablishes the equilibrium of the good old ways. The Best Years of Our Lives began with war and ends with comedy's fable of time, "Happily ever after." The soldier in the second panel of Harald Damsleth's magazine cover is in a state of comedy too, but he hasn't yet reached the resolution of act 3. In the snowy waste of his act 2, he is awaiting further orders. And the magazine tells him: In your mittens, you are dressed differently. But angle your smile toward your mittens as if you, like the mittens, were a work of art. Then you will become the boy your smile has taught you to be: a good boy at last, permanently worthy of your home in a painting by Harald Damsleth.

If Viktor Shklovsky is right about art, that reassurance explains why Harald Damsleth's magazine cover can be so bad -- so sentimental in content, so inept in form -- and yet still exert a power over us. Art, says Shklovsky in "Art as Technique," defamiliarizes. It takes a bit of the world, cuts it off from its familiar associations by putting a frame around it, and then forces us to look. "Look!" art commands. "See how different this bit of the world has been all along, and how strange and full of wonder!" But comedy, including the unwittingly comic art of Harald Damsleth, tells us: the wonder is all bad, but it need not endure.

Only put on the white Tarnhelm marked with its healing rune, says comedy, and I will conceal your eyes while you look at the black mitten that makes you different. Then I will send you back, changed to ice by steel and rune, into the unchanged world that you thought, foolish boy, would let you die.

*

Sources:

"Harald Damsleth." http://www.damsleth.info/biografi/biografi.htm, with included links "Før krigen," "Under krigen," and "Etter krigen" ("Before the war," "During the war," and "After the war")

Jakobsson, Sverrir. "On the Road to Paradise: 'Austrvegr' in the Icelandic Imagination." http://www.dur.ac.uk/medieval.www/sagaconf/sverrir.htm