A limit like the Vail

Unto the Lady's face -

But every Mesh - a Citadel -

And Dragons - in the Crease -

-- Dickinson, Fr554, "I had not minded walls"

Search This Blog

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

The black and white idea

1

William M. Van der Weyde,

Electric Chair at Sing Sing, ca. 1900

Great Photographs from Daguerre to the Great Depression

(Mineola, NY: Dover, 2008), image 091

Click to enlarge.

2

Irving Penn,

Vogue, April 1, 1950

3

"A mask will enable me to substitute for the face of some commonplace player, or for that face repainted to suit his own vulgar fancy, the fine invention of a sculptor, and to bring the audience close enough to the play to hear every inflection of the voice. A mask never seems but a dirty face, and no matter how close you go is still a work of art; nor shall we lose by staying the movement of the features, for deep feeling is expressed by a movement of the whole body. In poetical painting and in sculpture the face seems the nobler for lacking curiosity, alert attention, all that we sum up under the famous words of the realists 'vitality.' It is even possible that being is only possessed completely by the dead. . . ."

-- William Butler Yeats, introduction to Certain Noble Plays of Japan, by Ezra Pound and Ernest Fenollosa. 1916. Pound and Fenollosa, The Classic Noh Theatre of Japan (New York: New Directions, 1959), 155.

4

The black and white idea: straps and stripes and a black veil over a whitened face, retouched in the zone of transmission between the face and its image. Art as pyrotechnician of an explosion of high spirits: the April Fool's Day feeling that to put on the mask is never to die, let alone to experience curiosity or alert attention.

Bars of a portable prison. High-contrast loss of the middle ranges of emotion. Veil as barrier to whatever might be external to the self, a world that the veil has successfully excluded from notice by the masked face.

The black and white idea, at intervals before the death of Martin Luther King.

Sunday, January 17, 2010

Charis Weston, 1914-2009

Charis Wilson Weston, Santa Cruz, 2005

by Adrian Mendoza

See also

and

http://jonathan-morse.blogspot.com/2009/07/body-language-muse-of-reading.htmland

http://jonathan-morse.blogspot.com/2009/06/entirely-impersonal-lacking-in-any.html

Tuesday, January 12, 2010

Privacy and memory: an exchange with Susan Schultz

SS to JM:

And you've read about Walker Evans in Alabama in 1936: cold, aloof, making no effort whatever to conceal his contempt for the people he was making immortal. But oh boy no I do not want to relinquish my memory of what he achieved. In practice the call is hard, and you make it harder still.

But you begin broaching an idea about the difference between taking somebody's picture and writing about her. Are you going to develop that? I don't see much distinction myself between the two practices.

SS to JM:

I don't see myself doing what Frank and Arbus were doing, but perhaps I'm idealizing it. Even more complicated are the profound effects of these pieces on people like you, which matter, though yes, I do see the intrusiveness of it all.

I also think hardly anyone in the world will know of whom I write on Country Lane in Arden Courts.

But to think about, yes!

You seem to come down on the privacy end of things . . .

JM to SS:

In principle I do, yes, and I think it's an easy call. You wouldn't like it, for instance, if Robert Frank were to visit your mother in her Alzheimer's home and then publish her picture captioned "An American." You'd feel simplified, misrepresented, appropriated, exploited, objectified, and all kinds of other things too. And from Robert Frank it's an easy slide down a slippery slope to Diane Arbus, paparazzi with long lenses, the Church of Scientology, and the pro-life movement with its charming habit of publishing pictures of abortion providers' children just in case something should heh heh happen. A useful essay to read about all this, I should think, is Orwell's "Benefit of Clergy."

And you've read about Walker Evans in Alabama in 1936: cold, aloof, making no effort whatever to conceal his contempt for the people he was making immortal. But oh boy no I do not want to relinquish my memory of what he achieved. In practice the call is hard, and you make it harder still.

But you begin broaching an idea about the difference between taking somebody's picture and writing about her. Are you going to develop that? I don't see much distinction myself between the two practices.

SS to JM:

I don't see myself doing what Frank and Arbus were doing, but perhaps I'm idealizing it. Even more complicated are the profound effects of these pieces on people like you, which matter, though yes, I do see the intrusiveness of it all.

I also think hardly anyone in the world will know of whom I write on Country Lane in Arden Courts.

But to think about, yes!

Vanishing from the archive, deleting from memory

While she was chronicling her mother's descent into dementia, the poet Susan Schultz received an official letter politely demanding that she stop saying names. "Frequently," said the letter, "our patients and families blog about their stay at our centers. However, we must comply with HIPAA regulations. When we notice that other patient's names are mentioned, we ask that you edit any identifiable information out of your blog. That can include names, their hometowns, etc."

http://tinfisheditor.blogspot.com/2010/01/in-defense-of-using-proper-proper-names.html

A legal guide for writers told Schultz a hypothetical anecdote about a waitress named Linda who could sue someone who referred to her as Linda, and Schultz complied with the demand and changed the patients' names.

But that turned out to be painful. Thinking about the pain, Schultz wonders now:

Here's a photographic corollary.

In 1980, Howell Raines of the New York Times revisited the three poor Alabama families of whose lives James Agee and Walker Evans made immortal art forty years earlier in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Those forty years, it turned out, had reduced Agee's gusty prose to sentimental fiction. The pathetic little girl whose imminent death Agee movingly predicted, for example, was still alive in 1980 -- and a high school graduate, and six feet tall, and full of hatred for the artists who had once, long ago, picked up her tiny body, made it into a specimen, and then dropped it back into the dirt of Hale County, Alabama, and driven away.

As of 1980, too, Evans's photographs were gold on the exchanges of the art world, but that busy creation of wealth yielded the Woodses and Rickettses and Gudgers (or, to speak their unremembered "real" names, the Fieldses and Tingles and Burrroughses) not a nickel. About that conversion of life to exchange value, Raines was accurately ironic.

But reader: which work of art are you likelier to remember a year from now -- Raines's piece of prose or its pretext, this image? What happened to your decent reticence before this face?

http://tinfisheditor.blogspot.com/2010/01/in-defense-of-using-proper-proper-names.html

A legal guide for writers told Schultz a hypothetical anecdote about a waitress named Linda who could sue someone who referred to her as Linda, and Schultz complied with the demand and changed the patients' names.

But that turned out to be painful. Thinking about the pain, Schultz wonders now:

. . . why my stubbornness about names? Yes, the waitress named Linda might easily be transposed to the waitress at a similar restaurant with another ordinary, mid-20th century name. If the writer is out to defame Linda, who yelled at her child when the child spilled her ice water, then perhaps the writer needs some protection from the Linda who has not protected herself with due patience. But if Linda is in an Alzheimer's home, where her sole possessions are a few family photographs, some clothes, a handbag and her name? Easy enough to change the name, but I would argue that there are good reasons also for keeping it. To change a name is to create a secret, open or shut. To change a name is to change an identity (when I see a Linda in my mind's eye, she's not a Cynthia). When I hear the name Susan addressed to someone other than myself, I know I'm in the neighborhood of another woman born in the mid-50s to the mid-60s; our name is a generational marker. Maybe if I changed that name to Janet or Ruth, it would have a similar resonance. But maybe leaving the name alone, in the context of the Alzheimer's home, is an assertion that something of this person remains as it was. And, that if that person is now unrecognizable as "herself," she is still related to that earlier person in ways stronger than just the body.

Here's a photographic corollary.

In 1980, Howell Raines of the New York Times revisited the three poor Alabama families of whose lives James Agee and Walker Evans made immortal art forty years earlier in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Those forty years, it turned out, had reduced Agee's gusty prose to sentimental fiction. The pathetic little girl whose imminent death Agee movingly predicted, for example, was still alive in 1980 -- and a high school graduate, and six feet tall, and full of hatred for the artists who had once, long ago, picked up her tiny body, made it into a specimen, and then dropped it back into the dirt of Hale County, Alabama, and driven away.

As of 1980, too, Evans's photographs were gold on the exchanges of the art world, but that busy creation of wealth yielded the Woodses and Rickettses and Gudgers (or, to speak their unremembered "real" names, the Fieldses and Tingles and Burrroughses) not a nickel. About that conversion of life to exchange value, Raines was accurately ironic.

Four months before her death, Allie Mae struggled from bed to satisfy the British film maker who arrived in Alabama desperate for footage of her famous face. But when a Harvard senior showed up in her hospital room in Tuscaloosa, eager to complete his thesis on what it was like when James Agee came among the poor people, Allie Mae declined to say.

But reader: which work of art are you likelier to remember a year from now -- Raines's piece of prose or its pretext, this image? What happened to your decent reticence before this face?

That question could be terrible, I suppose. Fortunately, however, the archive has spared you. Its technology hints at terrible thoughts, but then it helps you delete them from your memory.

In my university's library, the microfilm archive of The New York Times has deteriorated to the point where some print is no longer legible, and the microfilm readers never could print images in any usable detail. When Nicholson Baker wrote a book about the scope and significance of losses like these, some optimistic librarians reminded him that the Web is all memory -- memory permanent and undying, inhumanly incapable of letting us humans forget.

But if you go to the online archive now in search of Howell Raines's essay, this is what you will find.

To read the words where image once was,

click to enlarge.

*

Sources and related reading:

James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Families. 1940; rpt. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2001. Print.

Nicholson Baker, Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Reading. New York: Random House, 2001. Print.

Dale Maharidge and Michael Williamson, And Their Children After Them: The Legacy of "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men": James Agee, Walker Evans, and the Rise and Fall of Cotton in the South. New York: Seven Stories Press, 1990. Print.

Howell Raines, "Let Us Now Revisit Famous Folk." New York Times Magazine 25 May 1980.

Saturday, January 2, 2010

Home front art: familiarizing the defamiliar

The girl in her warm, bright room is quiet, clean, and orderly. Her hair is in place and her white sleeves are unstained. Neither weeping nor smiling as she contemplates a neatly framed photograph of a soldier in a steel helmet, she sits at a tidy, well appointed desk and calmly writes a letter. Outside her window, the weather is improbably clear for a winter day in Norway. The horizon is enclosed by a crisply outlined mountain, and the landscape is thickly blanketed in a snowfall which gently rounds all outlines. It spreads virginity everywhere. The two sets of ski tracks that cross it are only another aspect of the virginity; presumably they led the girl safely home. There in her home she is now writing. Except for the motion of her pen over the snowy paper, all in her world is still. In this cosmos of calm there is neither motion nor detail; only thick clear static unambiguous outline.

On the snowy companion cover of the magazine that brings him his picture of the girl, the soldier reads his letter. Behind him is a shattered tree; in front of him, at the ready, is his rifle, a Karabiner 98. His eyes are hidden by his helmet, but on his mouth is a half-smile. His uniform is white camouflage, but his hands are swaddled in black. It is (and the angles of helmet and letter direct our eyes to it) the black of a pair of mittens, knitted in a traditional Norwegian snowflake pattern. Like the girl's world, the soldier's world is unmoving. There is no retreat on this front; only, in the long shadows of a northern winter, white letter and black mitten and the stationary idea of home.

The soldier would have been a member of Hitler's SS Wiking Division, a body of Norwegian fascist volunteers that spent most of World War II on the Russian front. The magazine which helped him see himself and his girl this way, static obverse and reverse, was published for him by the Nasjonal Samling ("National Gathering"), Vidkun Quisling's Norwegian Nazi party. Its full title was Austrvegr: manedsblad for frontkjempere og germansk landtjeneste -- that is, "Austrvegr: A Monthly for Front-Line Fighters and Germanic [not 'German'] Servicemen." However, that word in the main title, Austrvegr, in its runic font on the background of a highway sign, isn't Norwegian but Old Norse. The ancient term literally translates to "Eastward Road," but in the sagas it refers to the east generally and, often, to Russia specifically (Jakobsson).

Like the philological and racial term germansk in the magazine's subtitle, the magazine's antique name is probably symptomatic. I'd guess that it could be placed in a continuum with the Malatesta cantos of Ezra Pound, the vast collection of Americana at the Henry Ford Museum, T. S. Eliot's fugitive Criterion essays in mystical praise of folk dancing, and the archetypal psychology of Jung. All such accumulations of feeling can be considered expressions of twentieth-century conservatism's yearning for the mythic and the authentic -- and a soldier taking part in a long retreat across a white hell certainly would have a mind full of yearning. It seems to have been the mission of Austrvegr to translate that yearning into determination and confidence. For that morale-building purpose, the magazine's title spoke the language of Norway's Viking myth, and its covers illustrated that language in broad strokes containing and controlling washes of unambiguous primary color.

The cover's illustrator, Harald Damsleth (1906-1971), was helped to paint those broad strokes by an aesthetic which shaped itself around his politics. With a German mother, a German wife, and an education from a German school of commercial art, Damsleth had joined the Nasjonal Samling as early as 1933, and after the German conquest of Norway in 1940 he became one of the Quisling regime's most prolific propagandists. Many of his former colleagues in Oslo's advertising and publishing worlds ceased to deal with him, but in his wartime designs, from posters to postage stamps, he reached back for strength to an ancient source in the Nasjonal Samling's pagan sun-circle emblem.

Image and subsequent information from "Harald Damsleth."

Click to enlarge.

On the snowy companion cover of the magazine that brings him his picture of the girl, the soldier reads his letter. Behind him is a shattered tree; in front of him, at the ready, is his rifle, a Karabiner 98. His eyes are hidden by his helmet, but on his mouth is a half-smile. His uniform is white camouflage, but his hands are swaddled in black. It is (and the angles of helmet and letter direct our eyes to it) the black of a pair of mittens, knitted in a traditional Norwegian snowflake pattern. Like the girl's world, the soldier's world is unmoving. There is no retreat on this front; only, in the long shadows of a northern winter, white letter and black mitten and the stationary idea of home.

The soldier would have been a member of Hitler's SS Wiking Division, a body of Norwegian fascist volunteers that spent most of World War II on the Russian front. The magazine which helped him see himself and his girl this way, static obverse and reverse, was published for him by the Nasjonal Samling ("National Gathering"), Vidkun Quisling's Norwegian Nazi party. Its full title was Austrvegr: manedsblad for frontkjempere og germansk landtjeneste -- that is, "Austrvegr: A Monthly for Front-Line Fighters and Germanic [not 'German'] Servicemen." However, that word in the main title, Austrvegr, in its runic font on the background of a highway sign, isn't Norwegian but Old Norse. The ancient term literally translates to "Eastward Road," but in the sagas it refers to the east generally and, often, to Russia specifically (Jakobsson).

Like the philological and racial term germansk in the magazine's subtitle, the magazine's antique name is probably symptomatic. I'd guess that it could be placed in a continuum with the Malatesta cantos of Ezra Pound, the vast collection of Americana at the Henry Ford Museum, T. S. Eliot's fugitive Criterion essays in mystical praise of folk dancing, and the archetypal psychology of Jung. All such accumulations of feeling can be considered expressions of twentieth-century conservatism's yearning for the mythic and the authentic -- and a soldier taking part in a long retreat across a white hell certainly would have a mind full of yearning. It seems to have been the mission of Austrvegr to translate that yearning into determination and confidence. For that morale-building purpose, the magazine's title spoke the language of Norway's Viking myth, and its covers illustrated that language in broad strokes containing and controlling washes of unambiguous primary color.

The cover's illustrator, Harald Damsleth (1906-1971), was helped to paint those broad strokes by an aesthetic which shaped itself around his politics. With a German mother, a German wife, and an education from a German school of commercial art, Damsleth had joined the Nasjonal Samling as early as 1933, and after the German conquest of Norway in 1940 he became one of the Quisling regime's most prolific propagandists. Many of his former colleagues in Oslo's advertising and publishing worlds ceased to deal with him, but in his wartime designs, from posters to postage stamps, he reached back for strength to an ancient source in the Nasjonal Samling's pagan sun-circle emblem.

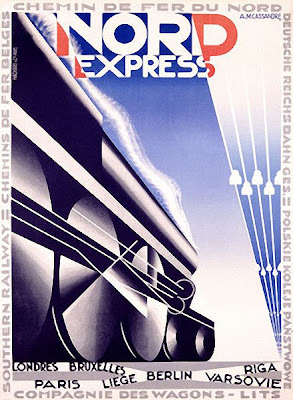

And here's something that looks like a difference but isn't: before 1940, Damsleth was an internationalist. In his prewar work, he was a magpie of Art Deco: a collector of angles and fonts and motifs whose composite designs almost amounted to plagiarism from such primary creators as A. M. Cassandre.

By Damsleth

By Cassandre. Click to enlarge.

Such unoriginality can be historically educational. The derivative, secondary forms that make up Damsleth's Art Deco seem to mean that by the time modernism reached Norway in the 1930s, it had become canonical. Because it could now be imitated in recognizable form, because it could now be understood by allusion, it could be thought of as a tradition, no more startling than the six-pointed snowflake star on the Nazi soldier's mitten. By the time they reached Damsleth's studio, the streamlines on Upton Sinclair's racing car were no longer functional but superficial. The demand they made on Norway's way of seeing was no longer an engineer's daring imperative but the merely temperamental mood swing of a fashion trend. When the time came for Norwegian style to change again, streamlining receded without a fuss before the newer trend of the folksy and the mythic.

And of course there's nothing specifically Norwegian or Nordic or Nazi about the theme of Damsleth's cover for Austrvegr. Far from home and in danger, anyone will fantasize about the place where he longs to return, and he will wish the place to be a wise, sheltering mother to his moods, outwardly impassive but secretly knitting fuzzy mittens just for him. In the United States, for instance, one of the most popular movies produced during World War II, Since You Went Away, depicts home as an impeccably hierarchical place, with Claudette Colbert and Monty Woolley dispensing their words of wisdom not in American demotic but in the Received Standard English of the Mother Country. Another blockbuster, The Best Years of Our Lives, introduces us at the start to three returning veterans, reveals them to have been respectively a member of the prewar upper class, a member of the prewar middle class, and a member of the prewar lower class, and then observes as the American class system reestablishes itself over their lives.

And, of course, The Best Years of Our Lives ends, as its art requires it to, with a wedding and a promise of more weddings to come. As Albert Cook says in The Dark Voyage and the Golden Mean, comedy is conservative. It starts with a stable social structure, upsets it by changing it (in comedy, different means bad), and then reestablishes the equilibrium of the good old ways. The Best Years of Our Lives began with war and ends with comedy's fable of time, "Happily ever after." The soldier in the second panel of Harald Damsleth's magazine cover is in a state of comedy too, but he hasn't yet reached the resolution of act 3. In the snowy waste of his act 2, he is awaiting further orders. And the magazine tells him: In your mittens, you are dressed differently. But angle your smile toward your mittens as if you, like the mittens, were a work of art. Then you will become the boy your smile has taught you to be: a good boy at last, permanently worthy of your home in a painting by Harald Damsleth.

If Viktor Shklovsky is right about art, that reassurance explains why Harald Damsleth's magazine cover can be so bad -- so sentimental in content, so inept in form -- and yet still exert a power over us. Art, says Shklovsky in "Art as Technique," defamiliarizes. It takes a bit of the world, cuts it off from its familiar associations by putting a frame around it, and then forces us to look. "Look!" art commands. "See how different this bit of the world has been all along, and how strange and full of wonder!" But comedy, including the unwittingly comic art of Harald Damsleth, tells us: the wonder is all bad, but it need not endure.

Only put on the white Tarnhelm marked with its healing rune, says comedy, and I will conceal your eyes while you look at the black mitten that makes you different. Then I will send you back, changed to ice by steel and rune, into the unchanged world that you thought, foolish boy, would let you die.

*

Sources:

"Harald Damsleth." http://www.damsleth.info/biografi/biografi.htm, with included links "Før krigen," "Under krigen," and "Etter krigen" ("Before the war," "During the war," and "After the war")

Jakobsson, Sverrir. "On the Road to Paradise: 'Austrvegr' in the Icelandic Imagination." http://www.dur.ac.uk/medieval.www/sagaconf/sverrir.htm

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)