Of course progress is dignified. We used to transport ourselves in a silly, old-fashioned way, says progress, but now both of the wheels on our bicycle are the same size, as is only proper. Using that moral fact to advertise refrigerators in 1931, the Electrolux Corporation summons us to recall the apposite moment in Tennyson’s

Idylls of the King when the dying Arthur surveys the universe and his and our place in it.

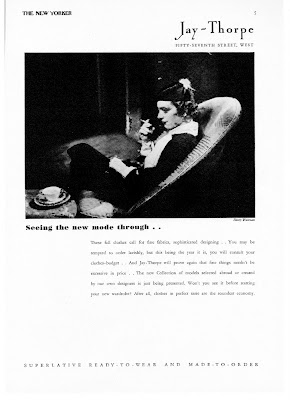

Click to enlarge.

This advertisement appeared on page 58 of

The New Yorker for September 12, 1931. On the next page begins Morris Markey’s article “DO-X,” the narrative of a flight in one of the 1930s’ great fantasy vehicles.

Wikipedia provides us with the fantasy in synopsis. With the idea of crossing the Atlantic by air on a regular schedule, the German engineer Claude Dornier conceived and then constructed an enormous twelve-engined seaplane, the Dornier Do-X. However, it entered service in 1929, the first year of the Great Depression. Only three years later it was retired, and the two other Do-X's that followed it down the assembly line vanished from history almost without a trace. Perhaps the best way to visualize any of them now is by way of a boy’s introductory tutorial to the dreams he will begin experiencing at puberty. The number in the upper right corner of this image refers to a suitable age for the boy. Numbers preceded by dollar signs will follow at a later stage of development.

But for nine months, from August 1931 to May 1932, that first Do-X was moored in New York, at what is now LaGuardia Airport, and there it was available to the senses of adults as it lifted them into the air for what must have been, for most of them, the first flight of their lives. It was one of those excursion flights that

The New Yorker’s Morris Markey helped his readers realize, and in the magazine his words are surrounded by images harmonizing with the psychic economy of the era that was then giving place to new.

Earlier in the magazine, for instance, a reader would have seen an advertisement for the Pitcairn Autogiro, a tiny short-takeoff-and-landing airplane which was one of the precursors of the helicopter. Crafted as carefully as the autogiro itself, its advertisement comes to us incorporating a parenthetical concession (“after the necessary training”), a chiasmus in conclusion, and an evoked setting entirely suitable for reading

The New Yorker. To

The New Yorker, the copywriter for Pitcairn Aircraft has confided:

Its ability to climb steeply and to take off and land in small areas, make it the craft that is practical, after the necessary training, for the personal use of sportsmen and business men. Many country estates have room in which the Pitcairn Autogiro can take off and land. From such homes, one may start upon a day’s sport or business trip, without first making the journey to a large airport. Polo fields, golf clubs and many other areas become available for landing an Autogiro, to save time and trouble for those who take to the air to save their time. (35)

Now, the year when the refrigerator’s quotation from Tennyson and the autogiro’s Gettysburg cadences entered read consciousness was 1931, the long sickening moment when the banks finally collapsed and it became obvious that the Great Depression was now a fact from which there would be no awakening into the light of dream. Some of

The New Yorker’s advertisers took note of that change in the psychic weather, and one of them reacted with a verb expressing resignation and endurance: "to see [something] through."

But within the covers of the magazine, that early observation was still an exception. It and Morris Markey's article about the Do-X are about the skeleton beneath the skin, but as of September 1931 most of the rest of

The New Yorker still understood reality to be a mode of presenting oneself as surface. It is that preoccupation with the external, perhaps, which makes us notice as exceptional the moment when Markey passes through the door of the Do-X and into its penetralia.

We climbed from the edge of the tender to the surface of the lower stub wing which thrust out bluntly from the hull at the waterline. Its surface curved gently, and it served the purpose of a deck. On the deck stood the ship’s master, Fritz Hammer, to greet us. He bowed and shook hands with quaint German courtesy, and two or three of his officers led us to the main entranceway. (59)

From the door, Markey entered the Do-X’s quiet, luxurious passenger compartment. From there he ascended to the airplane’s upper deck, where the pilot sat behind vast clear windows, bathed in light, “in a broad, deep chair, with an immense wheel in his hands . . . in a blue uniform with an immaculate white officer’s cap” (62). But then:

The engineer touched my arm. He was an American, for the twelve engines are of American manufacture. He beckoned me to follow him, and in a moment I had gone aft through the chartroom into the engine-room. The sight was stunning. We were now within the hollow body of the wing itself, and here was the essence of the Teutonic machinal, a thing out of some dark and iron romance.

[. . .]

I peered down the dark tunnel that the wing made as its hollow vastness reached out to ride upon the air. And there, on either side, were crouched gnomelike figures in brown clothing with brown leather helmets pulled down tight over their heads. They looked upward in the dim light, some of them fifty feet out from the body of the ship, peering through little openings at the engines above them. (62)

In 1931 it took a crew of seventeen -- some of them tall and in white hats, others dwarfish and in brown -- to force the Do-X across the surface of Flushing Bay and into the air. The same year saw publication of Aldous Huxley’s

Brave New World, with its image in the text of a dwarf Epsilon elevator man locked in his cage and its cover illustration of a globe-circling airplane.

And two years after that, in the first year of the Third Reich, the German post office would issue a series of charity surcharge stamps depicting the heroes of Richard Wagner, who had turned a mythology of blond heroes and dark dwarfs into a music. "The DO-X climbed very steeply then," Morris Markey noted right after his takeoff in 1931. "Steeply and very rapidly, with the engines moaning like the continuous song of a single 'cello note" (61).

But Markey's own prose does nothing with its startling phrase "the Teutonic machinal." In Markey's hands, it isn't yet anything more than a cliché left over from the Great War. As of 1931, likewise, most of Markey's

New Yorker colleagues still wrote words whose feet were on Fifth Avenue's ground. Reading those words, I try to translate them as survivals from a different place and time. There aren't many instances left that can still be read, but perhaps one is the text remaining on page 65. After the bombs fell on Europe, those words survived in all their magnificent silliness because they declined to turn away from the mirror and look up at the new thing arriving from above.

How good it was to believe that changing the old order was only a matter of replacing one mode with another as the seasons changed on solid, unchanging earth. How good it was to look into a mirror and know that nothing outside its frame really existed. How good it might be to believe that a model airplane is nothing but a toy: something that exists and is believed in only during a stage of development, and only for a time.